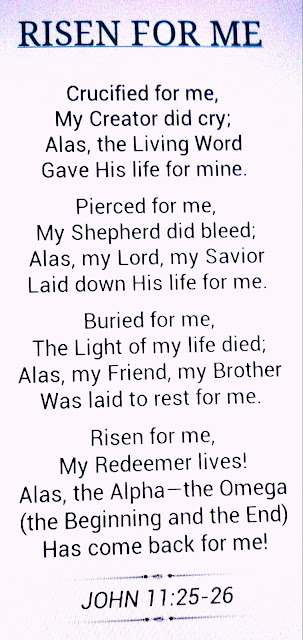

RISEN FOR ME

#HEISRISEN!

The Cross of the Moment

“[W]e are perpetually disillusioned. The perfect life is spread before us every day, but it changes and withers at a touch.”(1) The author of this comment did not have the dashed hopes of a person weary of contemporary political promises or the daunting purposelessness of life. His was not the disappointment of a child after his once-adored video game lost its thrill or the dispirited outlook of a millenial overwhelmed with options and fearful of missing out on something vital. No, long before video games existed, long before Generation Y was disillusioned with Generation X or X with the Baby Boomers before them, disillusionment reigned nonetheless. A social commentator in the late 1920s made this comment about his own disillusioned culture, words which in fact came more than a decade after a group of literary notables identified themselves as the “Lost Generation,” so-named because of their own general feeling of disillusionment. In other words, disillusionment is epidemic. As humans who tell and hear and live by stories, the possibility of taking in a story that is bigger than reality is quite likely. (Advertisers, in fact, count on it regularly.) Subsequently, disillusionment is a quality that follows humanity and its stories around. Yet despite its common occurrence, disillusionment is a crushing blow, and the collateral damage of shattered expectations quite painful. With good reason, we speak of it in terms of the discomfort and disruption that it fosters; we frame the crushing of certain hope and images in terms of loss and difficulty. The disillusioned do not speak of their losses lightly, no more than victims of burglary move quickly past the feeling of loss and violation. Ferdinand Hodler, The Disillusioned One, oil on canvas, 1892. And yet, practically speaking, disillusionment is the loss of illusion. In terms of larceny, it is the equivalent of having one’s high cholesterol or a perpetually bad habit stolen. Disillusionment, while painful, is evidence which shows the myths that enchant us need not blind us forever, a sign that what is falsely believed can be shattered by what is genuine. In such terms, disillusion is far less an unwanted intrusion than it is a severe mercy, far more like a surgeon’s excising of a tumor than a cruel removal of hope. The crucifixion of the Son of God is something like this. The death of God? There are no categories with which to understand it. For those who first held hope in the person of Jesus, it was the same. The death of the one thought to be the Messiah? It was an event that leveled them with disillusioned agony. New Testament scholar N.T. Wright describes the force of this dissonance:

“There were, to be sure, ways of coping with the death of a teacher, or even a leader. The picture of Socrates was available, in the wider world, as a model of unjust death nobly borne. The category of ‘martyr’ was available, within Judaism, for someone who stood up to pagans… The category of failed but still revered Messiah, however, did not exist. A Messiah who died at the hands of the pagans, instead of winning [God’s] battle against them, was a deceiver.”(2) For those who loved Jesus most, it took time to see that it was not hope itself but their hopeful illusions that died with him on the cross. Everything they thought God was, every hope for a messiah wielding power and control, every image of God winning the battle and taking a stand against their oppressors, everything they thought they knew about religion, painfully, but mercifully died on a shameful, Roman cross. We, too, can bury our illusions with the body of God. But it is no simple journey. The powerful words of poet W. H. Auden describe what is often the case in a world filled with sickly sweet illusion: We would rather be ruined than changed; We would rather die in our dread Than climb the cross of the moment And let our illusions die.(3) Yet if we will allow it, this death can be far more than loss. While advertisers count on our moving from one dead illusion to another, the death of Christ tells a completely different kind of story, a demythologizing story, which cuts through the storied layers of illusion we continually create about ourselves, the world, and others. Within such a story, disillusionment is the precursor to nothing short of resurrection. And faith is the audacity to confront our illusions with the cross upon which we find a self-giving God. In the words of author Parker Palmer, “[F]aith is the courage to face into our illusions and allow ourselves to be disillusioned about them, the courage to walk through our illusions and dispel them. Faith…[is] a disillusioned view of reality…that lets the beauty behind the illusions shine through.”(4) Invited to bury our illusions with the body of Christ, we bury them with none other than the one who unites us to himself in life and in death. We may stand in painful disillusionment, but we stand with the vicarious humanity of the Incarnate Son. Thus, for any losses we mourn or graves of dead dreams and visions over which we lament, so we may stand equally aware that we will be mercifully startled by what emerges from the tomb.

Jill Carattini is managing editor of A Slice of Infinity at Ravi Zacharias International Ministries in Atlanta, Georgia.

(1) John Boynton Priestley, “The Disillusioned,” in The Balconinny and Other Essays (London: Methuen, 1929), 30. (2) N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 658. (3) W.H. Auden, Collected Poems (New York: Random House, 2007), 530. (4) Parker Palmer, “Faith or Frenzy: Living Contemplation in a World of Action,” The Clampit Lectures, 1972.

www.rzim.org. Copyright © 2018 Ravi Zacharias International Ministries, All rights reserved. Our mailing address is: Ravi Zacharias International Ministries

#HEISRISENINDEED

Comments

Post a Comment